by Rachel Bockrath

On the morning of June 26, 2016, we set out for the field, another day of collecting. The tops of the hills look like freshly made brownies, in colors of red, orange, grey, and even deep purple. It looks like the set of a movie taking place on another planet. The badlands are desolate, where ants are the dominant life form, but 55 million years ago this place was a forested swamp teeming with life. The 2016 CSU paleontology field school was searching for their fossilized bones and teeth.

The flattened washout areas, where rain erodes the soil, were the areas that I focused on. Typically, one sees the larger bones before the smaller, more informative teeth. So, I followed the streams of long bone shards hoping to come across some teeth. Teeth are the easiest way to identify the animal and then we can match the associated bone with them. I followed multiple trails of small bone shard, before they disappeared, one at a time into the badlands. At that point, I was getting pretty discouraged. Putting my heavy backpack down, I sat next to it and thought to myself, “you would have thought I would have found at least one tooth by now!” I looked to my left, and saw a jaw sticking out of the dirt. “Oh, there it is,” I said, aloud this time. As I inspected the fossil, it became clear to me that this beauty would not be surrendered easily. Kim Nichols is director of the field school and I knew I needed her advice on how to proceed. Leaving my backpack as a marker, I went looking for help. Up and down over the hills, I scurried until I found her and was able to ask her to help me quarry.

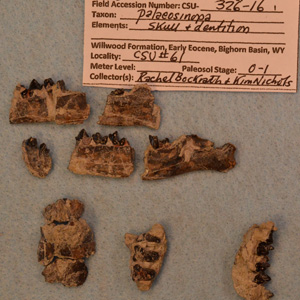

Upon further inspection, we saw more tooth tips sticking out of the ground and decided a plaster jacket was necessary. The plaster jacket would allow us to take the fossils back to the lab to make sure we recovered all of the pieces. Establishing a perimeter, we dug down and around in case more fossils that we could not see lie encased in the soil. We created the plaster jacket about a foot in diameter and 1-2 inches thick. With the plaster completed, it was all ready to transport back to CSU where we have successfully excavated and cleaned the specimen carefully.