Guatemala climate scientists look to tree rings for answers at CSU

Joshua Zaffos

This October, four researchers and technical scientists from INSIVUMEH Guatemala, the country’s meteorological service, spent a week in the Colorado State University Biogeography Lab counting the rings from cored samples of Caribbean pine trees through the lenses of stereo microscopes. The weeklong training, with Dr. Diego Pons, Assistant Professor of Geography, will help prepare INSIVUMEH and its technicians to perform this work on their own and better equip the agency to assess and model Guatemala’s climate forecasts. But dating tropical forests and measuring their growth through counting tree rings — the science of tropical dendrochronology — is no easy task.

INSIVUMEH technicians who visited CSU included Willson García, Hector Fuentes, Isabel González, and Jennifer Rivera. Agency Director Yeison Samayoa and Sub-Director Francisco Juárez also traveled to CSU for the workshop’s last few days. The project is supported by Guatemala’s Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (MARN) with a grant from the German development bank KfW. Pons, a climatologist who grew up and still does research and workshops in Guatemala, has worked with INSIVUMEH for more than 10 years.

“Building institutional capacity has always been key to ensure sustainability,” Pons said, “and that is now more important than ever when we, as scientists, are trying to understand the direction of our future climate. The Meteorological Service of Guatemala will now have the capacity to do research at timescales of centuries to millennia, helping the international community to understand tropical climate mechanisms better.

“I am happy to share what I was taught with the next generation of climatologists.”

“We’re training with Diego in dendrochronology techniques,” said González, INSIVUMEH Climate Change Coordinator, speaking in the Department of Anthropology and Geography’s Biogeography Lab, “but it’s hard because we can’t just count between thick and skinny rings.”

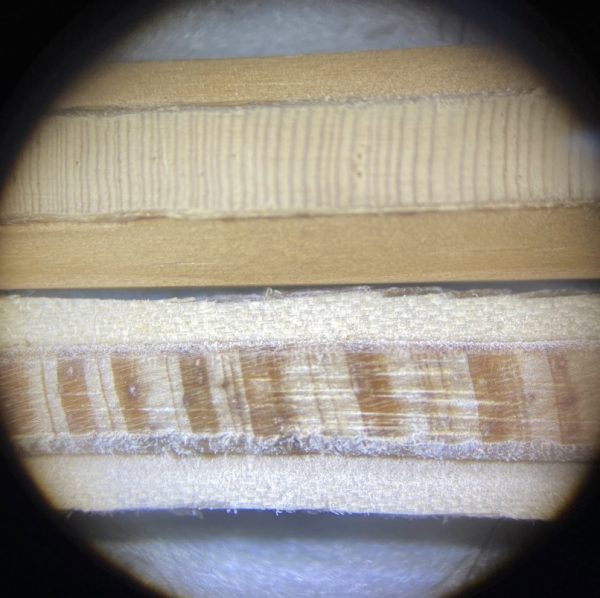

González is referring to the fact that if you peek into a microscope at a tree-core sample from a Colorado blue spruce, the tree’s rings — and age — will be easily discernible. Clear, darker lines alternate in a repeated pattern with lighter bands making it easy to read annual growth and to analyze for fires, drought, wet periods, or insect outbreaks that might show as irregular or off-color marks in the core. Try the same with a Caribbean pine from Central America and the exercise is more complicated. Due to the tropical climate and year-round moisture, tree rings are much harder to recognize or to distinguish from climate or weather events and bands vary in width.

As a result, Guatemala and other Latin American countries have utilized dendrochronology — and the proxy data it provides — much less than Northern Hemisphere countries. Through tree-ring analysis, scientists can recognize past precipitation and temperature patterns, drought frequency and intensity, and extreme weather events such as fires or hurricanes. That set of proxy data enables climate scientists to reconstruct past climates through models. This improved record of historical climates and their mechanisms could help improve forecasts of future climate-change scenarios.

In recent years, Guatemala’s mid-summer drought is lasting longer, said Willson García, Chief of INSIVUMEH’s Research and Meteorological Services Department, which affects agriculture, food security and rural people’s livelihoods. Now, INSIVUMEH’s technicians can potentially gather tree-ring data to model past mid-summer drought cycles.

Tree-ring analysis can also help determine if recent shifts in the range of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) – a band of atmospheric currents that account for rainfall periods in Central America and tropical regions around the world – resembles past changes and variability and what the long-term consequences might be. Ultimately, dendrochronology data can help improve INSIVUMEH climate forecasts and national projections about what warmer global temperatures or an altered ITCZ may mean for food production, water resources management, forest growth, and other important sectors.

“We are just starting to learn more about climate systems in Central America,” Pons said. “Tree rings provide a valuable record of past environmental and human events that we want to be able to read and understand so that we can learn from them and apply that knowledge towards future potential climate regimes.”

“I am happy to share what I was taught with the next generation of climatologists.” Diego Pons, Geography Professor

The Caribbean pine samples that the scientists assessed in the CSU lab may help address that question and hold fascinating clues about the country’s climatic and human history. Pons and colleagues, including González, completed a multiday expedition this past summer to reach the isolated stand of Caribbean pines in northeast Guatemala, surrounded by a much wider wilderness of subtropical humid forest. Along the way, the research team bushwhacked through ankle-deep swamps past snakes and other wildlife, slashing trails with machetes and futilely swatting away insects. The stand of pines is — climatically speaking — out of place in the wetter, lower-altitude region, and the 80-plus tree cores the team collected on the trek will help answer why.

The stand may be the naturally occurring relic of a once larger pine forest that grew during past, drier times, Pons said. But some people believe that the Maya people may have planted the trees centuries ago meaning their presence is as cultural as natural. Regardless, the trees and their rings could offer clues about what the duration, magnitude and frequency of drought in Guatemala might look if warming trends continue, and what that may mean for the people of Guatemala whose agricultural calendars – and food security – depend on rainfall patterns.

“It’s important to study climate for [the sake of] science,” González said, “but it’s also important to us to study for the people and for people in the future.”