Cohen Explores the Power of Dance in West Africa in New Book

In Infinite Repertoire, Anthropology Professor Adrienne Cohen weaves her insight as both ethnographer and dancer to examine how young women in Guinea are flexing new rights and roles through dance

August 9, 2022

Josh Zaffos

Smiling young men in plastic patio chairs play Djembe drums at one end of a circle of people along an unpaved city road in Conakry, Guinea, a West African coastal capital city of 1.9 million people. Dancers take turns, bounding into the middle of the circle, flexing and pumping their arms, engaging the beat. The movements are composed yet improvised, graceful and fierce. This late-afternoon gathering is known as a dundunba ceremony, a Guinean folk dance historically performed as a display of masculine strength and authority in rural villages. But all over Conakry these days, young women take equal part in ceremonies of this traditional “strong man’s dance.”

“Dundunba was originally a Maninka dance in which village men would whip themselves as a sign of strength,” said Adrienne Cohen, Assistant Professor of Cultural Anthropology at Colorado State University. Young women in Conakry have adopted the dance, without the actual whipping, and restyled dundunba’s signature pump move as their own show of strength.

Dancers in Guinea perform to earn money but dance is also what Cohen calls a “semiotic resource” in Guinea, meaning that, through their movements, performers mobilize embodied signs from the past in creative and aspirational ways. In the case of dundunba, she writes, “Younger people are taking this sign of male power and reinventing it in the urban present.”

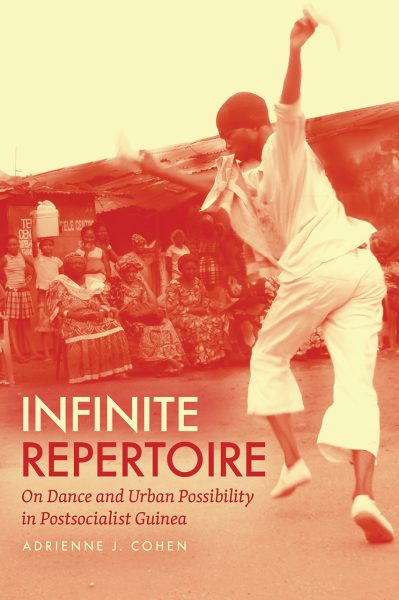

Cohen is the author of a new book (2021), Infinite Repertoire, On Dance and Urban Possibility in Postsocialist Guinea, which explores a long history of the connection between aesthetics and politics in Guinea. The book taps ethnographically into Conakry’s vibrant dance scene and shows how young urbanites, particularly women, are using dance to perform emerging social norms and gender roles. Infinite Repertoire builds from her four years’ living, working, dancing and, eventually, researching in Guinea, West Africa. The book has won the 2022 de la Torre Bueno First Book Award from the Dance Studies Association.

“Through many years immersed in Conakry’s dance scene,” Cohen writes, “I observed how virtuosic dancers could translate signs across time and space to make sense of their lives and to entail new futures.”

Cohen became invested in West African dance after being introduced to the music and movements during high school in Denver and then living in Mali as an exchange student. After graduating college, she booked a one-way plane ticket back to Mali to study dance. Within a few months, her music interests led her to Conakry, “a city pulsing with dance,” Cohen said. She stayed for three years, working as an art teacher during the days, apprenticing with a neighborhood dance troupe afternoons and evenings, attending stage-dance exhibitions and street performances whenever she could. Cohen also learned Susu, a West African language with few non-native speakers.

“With dance, I was watching people create beauty in a tough place [Conakry],” said Cohen. As she apprenticed and observed dance performances and ceremonies, she also began to recognize how dance is embedded in Guinea’s social and political landscape.

The thriving dance culture of Conakry has roots in the country’s postcolonial, socialist past. A one-time French colony, Guinea declared its independence in 1958. At the time, French President Charles De Gaulle allowed all colonies to vote to remain under France and its new constitution, or to become sovereign nations. Guinea, alone among the remaining French colonies, chose independence. Ahmed Sékou Touré stepped up as the new nation’s president embracing pan-African identity and pride in the wake of colonialism; De Gaulle responded by halting all French assistance.

Touré shaped Guinea into a socialist country and outlawed political parties other than his own. Over decades, he jailed, tortured, and killed his political opponents and limited foreign access to the country until his death in 1984. Since then, Guinea has experienced its share of political instability and repressive policies and leaders including a 2021 military coup that deposed the country’s democratically elected leader, President Alpha Condé. (Still, Guinea has had far less political violence and civil warfare than neighboring countries such as Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Ivory Coast.)

Touré’s socialist agenda also included using the performing arts as nationalistic propaganda to promote African culture around the world. His government created a nationalized network to train and recruit dancers and supported thousands of dance troupes – called “ballets” to assert equivalence with European dance – across Guinea. Les Ballets Africains, the country’s premiere national dance company, gained global fame and inspired black artists and activists around the world, including Miles Davis, Stokely Carmichael, and Miriam Makeba.

“All this history has added up to a really defiant and proud national culture that made Guinea different than its neighbors,” said Mike McGovern, Professor of Anthropology at the University of Michigan who has also done extensive research in Guinea and was Cohen’s doctoral advisor at Yale University. Under Touré, “the arts were considered one of the places where the Guinean government was going to bring back authentic African culture, heal the wounds of colonialism, and link to this new identity of socialism and pan-Africanism. Dance was about valorizing the nation and was part of the cause to rally the continent too.”

After Touré’s death, his successor Lansana Conté liberalized Guinea’s economy and reduced government arts and dance funding. Conté was in power for over two decades. As a result, few state-sponsored dance troupes remain in Guinea, but many ex-national artists founded private ballets, which are now the foundation of the capital city’s lively dance scene. Artists trained in those ballets animate daily street ceremonies across Conakry, which feature improvisational dance and mark important social occasions and rites of passage from marriages to baby-naming ceremonies to homecomings.

“Dance was always more than propaganda in Guinea,” said Cohen, adding that the book’s title takes inspiration from a Susu adage, “fare mu kolon ma,” meaning “dance cannot be known.” Guineans see dancers’ bodies and movements as a source of constant invention and transformation. [Read excerpt below.]

“Two arms and two legs, a torso and a head, somehow together can generate an unending lexicon of movement and semiotic potential,” Cohen writes in her book, “an infinite repertoire.”

During her first time living in Conakry, Cohen became determined to explore and interpret the meanings and motivations within modern dance ceremonies, which led her to pursue a Ph.D in Anthropology from Yale. Observing and rehearsing West African dance “is what first gave me the curiosity of an anthropologist,” she writes.

Cohen returned to Guinea in 2010 to conduct ethnographic research among dance troupe directors and dancers, launching the work for her doctoral dissertation and then book. Cohen spent the summers of 2010 and 2011 in Conakry. She returned for 9 months of research in 2012-2013, conducting more than 60 in-depth interviews, doing a daily apprenticeship with a prominent local dance troupe, Les Merveilles de Guinée, and attending dance ceremonies across the city.

“It’s not easy living in Conakry for three years,” said McGovern, mentioning frequent power outages and water shortages among other challenges of life in the Guinean capital. “You have to love it and you have to be tough, and Adrienne is tough, resilient and resourceful.”

Cohen opens her book with an anecdote of a woman dancer getting ready for a ceremony and deciding between wearing an African dress or something more “Zanet Zackson style.” Ceremonies are important sources of income and reputation for dancers. A woman who gains a reputation as a creative and talented soloist will “find name” and ultimately become a sought-after teacher and performer. Cohen explains the nuanced relationships between prestige, income, and creativity among Conakry performers, who have figured out how to build themselves socially and economically through dance.

Some elders around Conakry and outside the city told Cohen they are uncomfortable or upset seeing women performing these traditionally male power dances but many also recognize these ceremonies keep Guinean dance a living form of art. “Young people are finding super-creative ways to make Guinean dance potent today,” Cohen said. Her book is all about that potency among urban youth in a tough city.

One key theme that threads throughout the book is the way in which dance has long been politically salient in Guinea, from its rural manifestations in ritual, to its role as the media of a state-socialist regime, to its present position as a medium through which young people perform new ideas about what is or should be socially acceptable.

“[Dance] ceremonies are sites where people are testing out new social scenarios by performing them, gauging responses, and reworking them — all in a way that cannot be captured or condemned as a constative utterance might,” Cohen writes. By examining what is communicated in dance, she shows “how people who consider themselves ‘apolitical’ and typically do not participate in formal democratic deliberations about rights and responsibilities indeed play an active role in transforming societal norms and values.”

Cohen hopes that Infinite Repertoire provokes readers to consider how embodiment and affect shape our social and political worlds. The book also tells a story about the creativity and courage of young African urbanites, who are so often glossed in the media as either victims or vandals.

********

"Invitation: City of Dance"

Excerpt from Infinite Repertoire, On Dance and Urban Possibility in Postsocialist Guinea by Adrienne J. Cohen

Published with permission from The University of Chicago PressThe first thing a traveler sees upon arrival in Conakry's international airport is an eight-foot-tall hardwood statue of a drummer playing a djembe, the archetypal instrument of Guinean stage dance, or "ballet." He is smiling, head tilted back and drum thrust forward in a confident pose, towering over visitors and returning nationals as they queue to have their passports stamped. He is an emblem of Guinean nationalism. For elderly Guineans, he represents a time when the country was poised hopefully on the cusp of an independent and Africa-themed future; a time when music, dance, and theater were the primary communicative media of Guinea's socialist state (1958-84). That era witnessed the professionalization and nationalization of Guinean ballet -- so named to assert equivalence with European cultural forms -- and Guinea produced acclaimed national dance and percussion companies that toured the world to enthusiastic audiences. The socialist period in Guinea, while remembered fondly by performing artists, was also a time of extraordinary repression and extrajudicial punishment. From the perspective of the millions exiled or tortured under the socialist regime, that smiling statue belies a far more sinister history. The airport figure of a drummer playing the djembe therefore indexes an era differently inscribed into the collective psyches and bodies of Guinean citizens.

The statue also beckons to the many Guinean artists living abroad and their foreign students who regularly come to Conakry to be immersed in the ballet scene. These artists left when the government stopped supporting them after socialism. They are returning into an artistic world that has become invisible to officialdom, as ballet now exists almost entirely outside of formal avenues for cultural and economic production. Within this unacknowledged world -- which is sonically explosive and visually stunning -- Conakry is neither the failed city of development narratives nor a city where the recent embrace of democracy has made citizens feel "free" in comparison to the socialist past. Rather, it is a place where creativity has long negotiated with authority and where the body is a key site for producing political, metaphysical, and social power.