Out, Standing in the Field

CSU Paleontology Field School Rides Again in Summer 2021

Joshua Zaffos

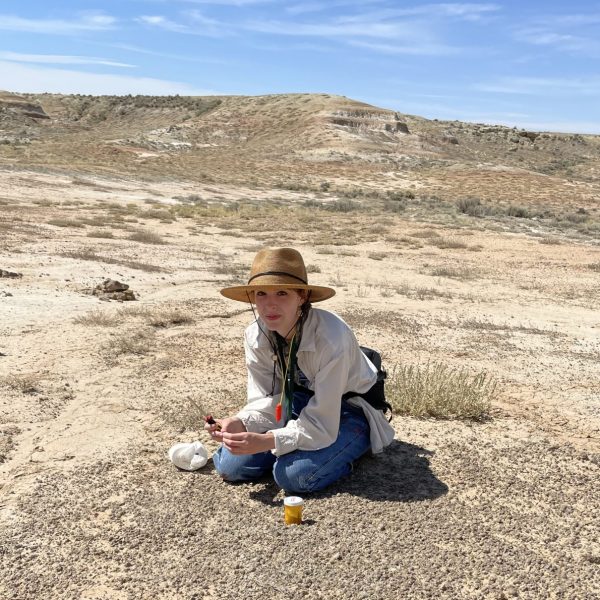

Colorado State University Anthropology student Natalie Freeman is doubled over, staring at the sun-scorched ground of the Wyoming badlands. A few yards away, Isabelle Dones, another CSU Anthropology major, scrapes her knees as she crawls along the rocky terrain. The nearly 100-degree midday July heat of the Bighorn Basin can be unrelenting and dangerous, but Freeman and Dones are far more stoked than staggered as they look for 55-million-year-old fossils in the dirt.

“Another one!” shouts Freeman, as she pulls what looks, at first, like an unremarkable dark pebble from the earth. In her palm, Freeman holds a very small fossil jaw with several tiny, pearly black teeth, belonging to an omomyid – one of the earliest primates in the fossil record. The long-extinct animal likely looked and behaved like modern tarsiers, half-foot-tall, big-eyed, furry critters whose appearance have been compared to Yoda. The students excitedly gaze at the fossil like it’s a rare gem.

“This helps us understand our evolutionary lineage, pre-dating previous hominin [human] species and the last common ancestor between humans and chimpanzees,” Freeman said.

The two CSU students took part in the Department of Anthropology and Geography’s 2021 Paleontology Field School this past summer. The program, led by Professor Kim Nichols and Dr. Thomas Bown, is one of a few – and quite possibly the only – undergraduate paleontology field schools in the U.S. that doesn’t center on dinosaurs or just cover fossil collection. Throughout the program, CSU undergraduates are immersed in lab preparation, fossil species identification, and museology techniques in addition to prospecting for specimens in the field. Each student also produces an individual field report on an extinct species of the Early Eocene Period using field data, lab data and library research.

"This is the model for professional paleontological investigations today,” Nichols said. “With the field school, we introduce undergraduates to all these components because a professional paleontology career requires field and lab research coupled with curation responsibilities.”

Started by Nichols and Bown in 2013, the field school prepares and takes students to the Bighorn Basin each summer to search for 56- to 52-million-year-old fossils of primates and the other vertebrates with which they lived. Back then – 10 million years after the extinction of the dinosaurs – the region was a subtropical forest, much like modern-day Florida, and included the ancestors of many modern mammals.

“It’s interesting to look at this place today and to then imagine oneself here as a swampy setting where all these animals were (running around),” said Freeman who is double majoring in Anthropology and Art and also completing the Certificate in Museum and Cultural Heritage Studies offered through Anthropology and Geography.

Students on the Paleontology Field School explore the fossil record and recognize how life proceeded following the demise of the dinosaurs, including the rise of prehistoric primates, like the omomyids, who are distant cousins to modern humans. Collected specimens and geologic data also provide a view into a past age of global warming, Nichols added, which can suggest to researchers how environments and species responded to rising carbon-dioxide levels and fluctuating global temperatures.

CSU’s Paleontology Field School occurs over four weeks each summer, opening with a series of lectures and activities inside Nichols’ Primate Origins Lab on campus. Students and instructors then head to north-central Wyoming to prospect for fossils across U.S. Bureau of Land Management badlands. After returning from the field, the students process and catalog the fossils from Nichols’ campus lab in order to complete their individual field reports on selected species. Curation and accession are performed in coordination with the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.

Pandemic restrictions in Summer 2020 scuttled the field school’s usual schedule since students couldn’t step inside the lab or go out in the field as a group. Instead, Nichols and Bown recorded lecture presentations, held virtual discussions and site visits, and focused final projects around Bown’s previously published research data on Bighorn Basin Early Eocene species, 56 to 52 million years old.

“There was a lot of getting to demonstrate your primate flexibility in all this,” Nichols joked about teaching a field program without getting into the field – or lab.

A year later, Nichols and Bown adapted recorded lectures and remote lessons and focused heavily on fossil identifications and descriptions in the lab. During 6-hour-long days in the lab, students stared through scopes and hand lenses at tiny, black-sheened fossil jaws, teeth, vertebrae, and other specimens, many the size of fingernails and pebbles. (All field-school participants received COVID vaccines before the program began.)

The long lab sessions paid off. Kneeling and crawling through the shadow-less Wyoming desert in midday, the field school’s eight undergraduate students – all women in 2021 – found those black-sheened fossils like practiced paleontologists, able to recognize tiny, half-buried fossils amid myriad rocks and soil.

“It’s one thing to see a fossil in the lab but it’s another to find it laying in the dirt,” Freeman said.

“The students really studied their [fossil] teeth in the lab,” added Nichols, noting that teeth are particularly valuable for paleontologists to identify species and their behaviors. “This is the first group who didn’t start out asking, Is this a fossil? Is this a fossil?’ It’s been remarkable and quality work.”

After returning from the field, students resume work on campus to catalog and measure their finds, gaining more extremely valuable skills and experience. In Nichols’ lab, students used brushes to more thoroughly clean the fossil specimens for analysis. Under microscopes, the students can determine and confirm species while also looking for fractures, bite marks, or other taphonomic features that serve as clues about ancient natural communities.

“The students are honing their skills of identification and getting an idea of what is involved with grad school,” Nichols said. “And with these fossils, we are also building a paleo biome at a very specific point in time,” meaning the field school and student discoveries are contributing to what scientists understand about the 56-52-million-year-old environment and the communities of ancient warming climates. Many Paleontology Field School students continue research they begin in summer through Capstone projects and the annual CSU Celebrate Undergraduate Research and Creativity Showcase.

“Working out in the field with [fossil] mammals, you ponder why species survived – why we survived,” said Isabelle Dones, who completed her Anthropology BA in Spring 2021 and plans to pursue research and a graduate degree in biological anthropology and primatology. “We’re working with teeth and fossils that are essentially what we’re descended from.”

The scorching sun and other conditions didn’t dull her and others’ excitement for paleontology. “I just told my family,” Dones said, “I think this is what I want to do.”

The CSU Paleontology Field School runs annually. Visit the program webpage to learn more, including information about and how to apply.